The Red Pyramid: Tomb or Ancient Ammonia Factory?

A Radical Reinterpretation of Egypt’s Oldest True Pyramid By Juan Fermín – EarthsLostHistory.com

The Red Pyramid at Dahshur stands as the world’s first successful true pyramid, built around 2600 BC for Pharaoh Sneferu. Mainstream archaeology calls it a tomb—albeit an empty one with no mummy, no treasures, and awkward internal access that makes burial rituals improbable.

But what if it was never meant to house a body? What if its three corbelled chambers, narrow connecting passages, and massive limestone shell were engineered as a staged chemical reaction vessel—specifically, an ancient high-pressure plant for producing aqueous ammonia, the ultimate fertilizer that turned Egypt’s marginal Nile floodplain into the ancient world’s breadbasket?

The interior layout is bizarre for a burial chamber:

- A long descending entrance passage from the north face.

- Two lower antechambers with high corbelled vaults.

- Short, tight upward passages leading to a high-offset third chamber.

- No sarcophagus, no inscriptions, no grave goods.

Yet this design perfectly matches a gravity-fed, pressure-assisted gas reactor:

- Lower chambers → Gas generation zone (steam reforming of organics or methane seeps with water to produce hydrogen-rich syngas).

- Narrow passages → Natural throttles that build pressure and drive gases upward.

- Upper chamber → Final synthesis and absorption zone, where hydrogen meets nitrogen over catalytic surfaces, forming ammonia that dissolves into water basins.

Independent researchers like Geoffrey Drumm (The Land of Chem) have entered the pyramid and reported persistent ammonia odors and directional wall staining—exactly what you’d expect from centuries of gas flow and chemical residue.

The Product: Aqueous Ammonia – The Secret to Egypt’s Food Empire

Ancient Egypt thrived on the Nile’s annual flood silt, but yields were limited by nitrogen availability. Natural sources like manure and urine helped, but a concentrated, controllable nitrogen fertilizer would revolutionize agriculture.

Aqueous ammonia (NH₃ dissolved in water) provides exactly that: direct ammonium ions for explosive plant growth. Applied to fields, it could push harvests far beyond natural limits—especially on higher, drier land away from the floodplain.

This explains Egypt’s legendary grain surpluses. Biblical stories of Joseph storing food during seven fat years to survive seven lean ones? That’s not just good management—it’s technological superiority. While neighbors starved during droughts, Egypt fed them... for a price.

The Eerie Modern Echo: Fritz Haber and the Red Pyramid

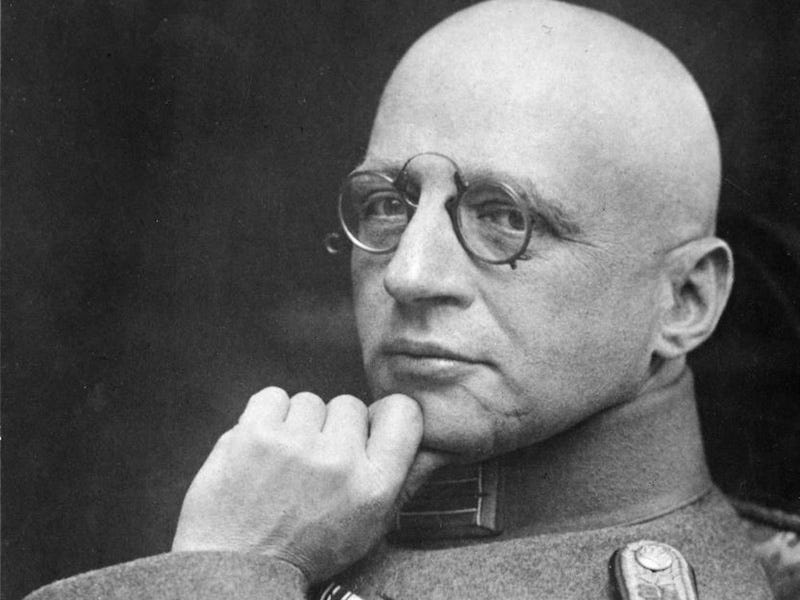

Fast-forward to the 20th century. Fritz Haber develops the high-pressure ammonia synthesis process (later industrialized as Haber-Bosch), feeding half the world’s population today.

Haber’s early lab reactors? Three-stage, high-pressure systems. And Haber? A documented pyramid enthusiast who visited Egypt multiple times.

The parallel is striking: an ancient three-chamber stone reactor producing ammonia... and a modern three-stage steel one, invented by a chemist obsessed with Egyptian monuments. Coincidence? Or lost knowledge resurfacing?

Why Hide a Factory Inside a Pyramid?

- Containment — The millions of tons of limestone withstand pressure pulses and thermal cycles.

- Secrecy — Sacred monumental facade protects proprietary technology.

- Scale — Only a mega-structure provides the volume for meaningful output.

The “tomb” narrative could be later overlay—ritualizing a pre-existing industrial core.

This isn’t fantasy. It’s a hypothesis that fits the evidence better than an empty tomb for a pharaoh who was supposedly buried elsewhere.

The Red Pyramid may not guard a king’s afterlife. It may guard the secret of how ancient Egypt fed the world—and dominated it.

What do you think? Was Dahshur an industrial complex disguised as monuments? Drop your thoughts below, and share this if you’re ready to question everything they taught you about the pyramids.

— Juan Fermín EarthsLostHistory.com